A Century of Light and Shadow, Oriental Opera Charm: 120 Years of China's Film Development

A Century of Light and Shadow:

120 Years of China's Film Development

In 1905, the birth of China's first film "Dingjun Mountain" marked the beginning of China's film history. Over 120 years of storms and changes, Chinese cinema has evolved from silent to sound, from black and white to color, from film to digital, and from local exploration to global reach. It not only documents the tremendous changes of the times but also constructs a unique visual aesthetic system with an oriental charm, becoming an indispensable part of Chinese culture.

Birth and Germination (1905-1931):

The Birth of Light and Early Exploration

In 1905, the Peking Opera short film "Dingjun Mountain", directed by Ren Qingtai and starring Tan Xinpei, was completed at Fengtai Photo Studio in Beiping. This film, which only contained three segments— "volunteer service", "dagger dance", and "battle scene" —was the first to combine China's traditional opera with film technology, marking the official birth of Chinese cinema.

Figure 1. Reconstruction of the shooting site of Dingjun Mountain

In the 1920s, a film market centered in Shanghai gradually took shape. Early filmmakers such as Zhang Shichuan and Zheng Zhengqiu founded the "Star Film Company" and produced works like "The Hardship of Husband and Wife" (1913) and "The Orphan Saves His Grandfather" (1923). These films were close to the lives of citizens, combining educational significance with entertainment, and laid the foundation for the exploration of commercial films in China.

During this era, most films were silent, relying on subtitles and actors 'body language to tell stories. Actors like Ruan Lingyu and Jin Yan rose to stardom through their masterful performances.' The Goddess' (1934, directed by Wu Yonggang) became a pinnacle of silent cinema, using delicate cinematography to portray the tragic fate of women from humble backgrounds.

Figure 2 "Goddess"

Awakening and Growth (1931-1949): The Age of Sound and the Rise of Left-Wing Cinema

In 1931, China's first sound film, "The Red Peony" (directed by Zhang Shichuan), was born. Although it used wax disc dubbing technology with rough sound quality, it achieved the leap from "silence" to "sound." Later, "The Song of the Fishermen" (1934, directed by Cai Chusheng) combined sound technology with realistic themes, becoming the first Chinese film to win an international award—the Honorary Award at the Moscow International Film Festival.

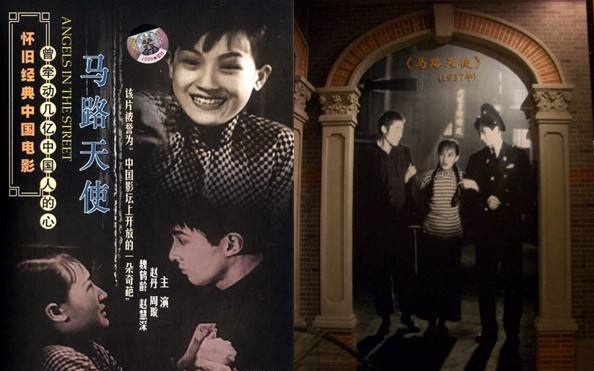

In the mid-1930s, influenced by progressive cultural trends, Xia Yan, Tian Han, and others served as screenwriters, producing works such as "Spring Silkworm", "Mad Stream", and "Street Angel", which focused on the suffering of the lower classes, criticized the dark reality, and conveyed progressive ideas. "Street Angel" (1937, directed by Yuan Muzhi) became a model of China's realist cinema with its blend of humor and compassion.

Figure 3. Movie poster of Road Angel

During the Anti-Japanese War, filmmakers ventured into inland regions and enemy-occupied areas to produce patriotic films like "The Eight Hundred Heroes" and "The Storms on the Frontier," boosting national morale. In 1947, Cai Chusheng and Zheng Junli co-directed "Spring River Flows East," a grand narrative that vividly depicted social transformations before and after the war. The film not only set a box office record at the time but also became a milestone in post-war cinema.

Figure 4 "Spring River flows east"

Transformation and Exploration (1949-1978): Red Narratives and Typification Attempts

After the establishment of New China, the film industry was incorporated into the national cultural construction system, with state-owned studios such as Changchun Film Studio and Beijing Film Studio being established. Films during this period were mainly revolutionary historical themes and realistic themes. Works such as "The White-Haired Girl" (1950), "The Red Detachment of Women" (1960, directed by Xie Jin), and "Forest Sea and Snowy Plains" (1960) created classic heroic images and formed a distinct "red film" style.

Figure 5 "Red Women's Army"

From the late 1950s to early 1960s, Chinese cinema witnessed a wave of diversified explorations. The 1959 film *Lin Family Shop* (directed by Shui Hua), adapted from Mao Dun's novel, delicately portrayed social transformations. Meanwhile, *Early Spring in February* (1963, directed by Xie Tieli) delved into the spiritual dilemmas of intellectuals, achieving remarkable heights in both visual aesthetics and nuanced character portrayals.

From 1966 to 1976, film production stagnated and only a small number of "model play films" were released. But some filmmakers remained committed to artistic pursuits, accumulating strength for the subsequent revival.

Recovery and Prosperity (1978-2000): The Fifth Generation Directors and the Beginning of Marketization

After the reform and opening up, film creation broke free from ideological shackles and ushered in the "new era film" boom. Works such as "Little Flower" (1979) and "Lushan Love" (1980) broke through the traditional narrative mode and integrated love and human nature thinking, becoming the memory of the times.

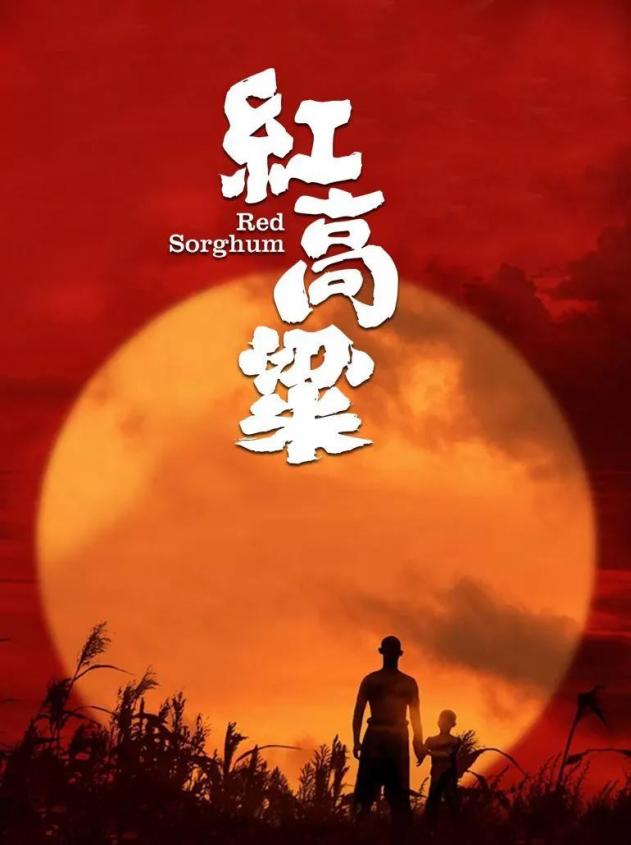

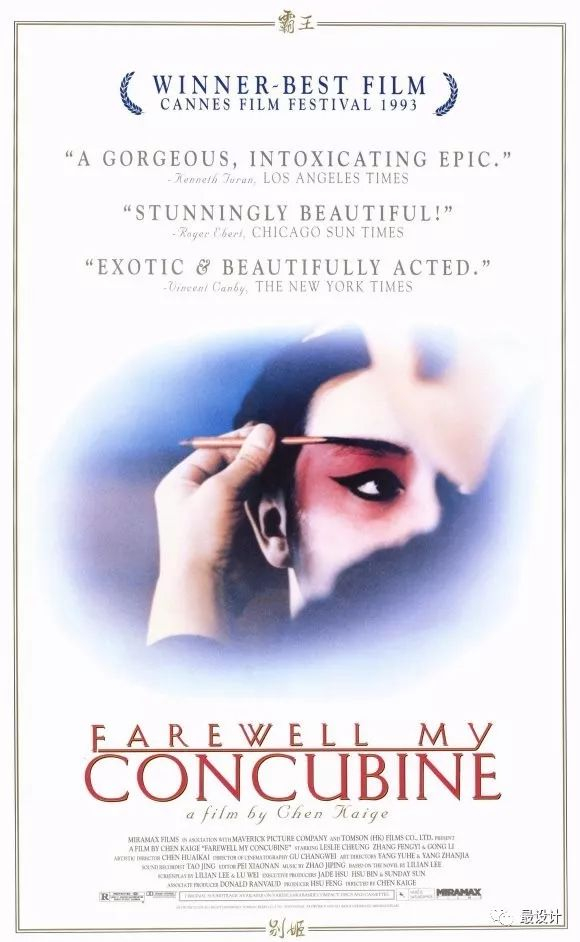

In the mid-1980s, Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, Tian Zhuangzhuang, and other "Fifth Generation directors" graduated from the Beijing Film Academy, shocking the film industry with their unique visual language and cultural reflection. In 1987, Zhang Yimou's "Red Sorghum" won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival with its intense colors and vitality, showcasing the national spirit and becoming a landmark work of China's cinema going global. In 1993, Chen Kaige's "Farewell My Concubine" explored human nature and the times with an epic scale, and remains the highest-rated Chinese film on Douban to this day.

Figure 6. Movie posters of Red Sorghum and Farewell My Concubine

In the 1990s, the film industry began to explore market-oriented operations. In 1997, Feng Xiaogang's "A and B" pioneered the concept of the "New Year's season" with a comedic style that catered to audience demands. Meanwhile, co-productions gradually emerged, laying the foundation for China's films to integrate into the international market.

Figure 7 "Party A and Party B"

Rise and Leap (2000-2025): Industrial Upgrading and Global Layout

Since the 21st century, China's film genres have become increasingly diverse. From the early 21st century, martial arts blockbusters like "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" and "Hero" pioneered the market, to comedies such as "Lost in Thailand" and "Goodbye Mr.Loser", action films like the "Ip Man" series, suspense films like "The Burning Sun" and the "Detective Chinatown" series, and animated films (including "Monkey King: Hero Is Back" and "Ne Zha: The Demon Child") flourishing across various genres, China's film industry has transformed from a single genre to a diversified ecosystem.

After 2000, China's film industry gradually freed itself from dependence on foreign technology. From the early introduction of international teams to explore standardized production processes, to works like "The Assembly" (2007) and "The Wandering Earth" (2019), breakthroughs were achieved in special effects production and narrative scale, marking a new stage in the industrialization of China's film industry. "The Wandering Earth" pioneered the genre of "China sci-fi films" and achieved both box office success and critical acclaim with its core theme of "a community with a shared future for mankind."

Figure 8. Scene effect of The Wandering Earth

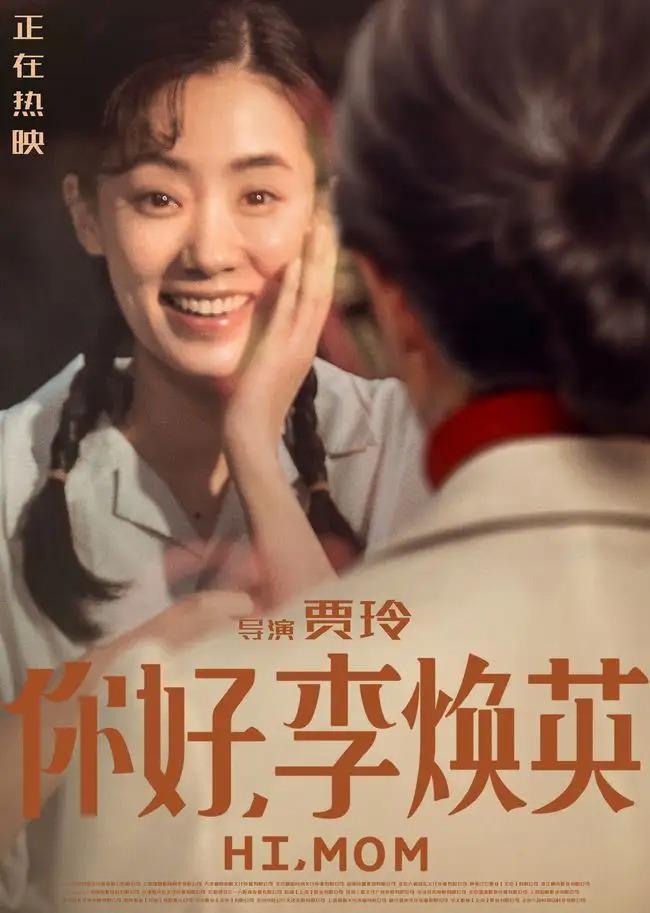

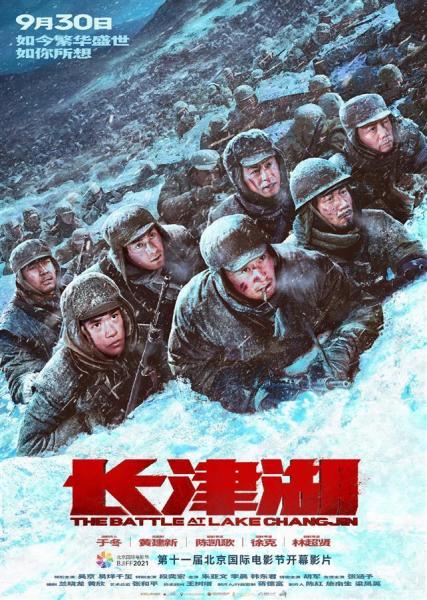

After 2010, China's film market became the world's second-largest, with box office revenue exceeding 64.2 billion yuan in 2019. Films such as "Wolf Warrior 2" (2017), "Hi, Mom" (2021), and the "The Battle at Lake Changjin" series repeatedly set box office records, demonstrating the strong vitality of the domestic market. Meanwhile, in 2000, Ang Lee's "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, and the success of Asian films like "Parasite" (2019, South Korea) also promoted cultural exchanges of Chinese films worldwide.

Figure 9 Movie posters of "Wolf Warrior 2", "Hi, Mom", and "The Battle at Lake Changjin"

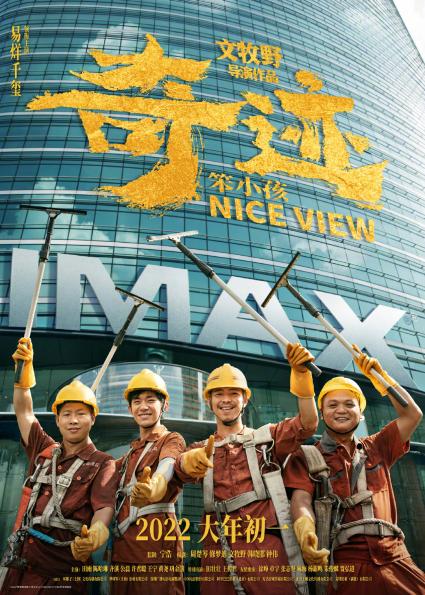

In recent years, the industry has demonstrated comprehensive development characterized by technological innovation, content upgrades, and ecosystem refinement. Content creation has established a creative orientation rooted in realism, branching through genre innovation, and nourished by cultural heritage. Mainstream films have transitioned from grand narratives to intimate empathy, with works like *Miracle: The Story of a Child* and *My Father's Generation* reflecting social transformations through ordinary people's stories. Adaptations of traditional culture continue to innovate, from the poetic essence of *Three Thousand Miles of Chang'an* to the mythological reinterpretation in the *Fengshen* series, achieving modern expressions of cultural heritage. The rise of young directors has introduced more distinctive creative perspectives, fueling sustained vitality within the industry.

Figure 10: Movie posters for "Miracle", "My Father's Generation", and "Three Thousand Miles of Chang' an"

In terms of technology application, digital technologies such as 4K/8K ultra-high-definition shooting, VR/AR immersive viewing, and AI-assisted creation have been deeply integrated into film production. LED virtual shooting and self-developed special effects software have been widely applied. The "The Battle at Lake Changjin" series, "The Legend of Deification Part 1" (2023), and "The Wandering Earth 2" have propelled Chinese cinema into a new stage of production combining virtual and real elements. The standardization and refinement of film production have continued to improve, achieving the core goal of technology serving content.

Figure 11 "Fengshen Part 1"

Over 120 years of cinematic evolution, Chinese cinema has progressed from simple photography at Beijing's Fengtai Photo Studio to today's industrialized production and global dissemination, witnessing a nation's cultural awakening and national rejuvenation. Each classic film is a microcosm of its era, and every filmmaker is a custodian of cultural heritage. At this new historical juncture, Chinese cinema is writing an Eastern cinematic legend with greater openness, more refined artistry, and deeper cultural roots.