A new century begins, a wave continues: 130 years of French film development

Since the Lumière brothers startled the first audience with the footage of L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat in the basement of Paris's "Grand Café" in 1895, French cinema has been intricately intertwined with the history of world cinema. Over the past 130 years, it has not only been an inventor of technology but also a perpetual innovator in art, consistently leading global film trends in aesthetics, technology, and philosophy. Its developmental journey is a magnificent tapestry woven from five brilliant, interconnected, and distinct chapters.

I. 1895-1910s: The Birth of Light and Shadow and the Embryo of Narrative

The starting point of French cinema is the starting point of world cinema. The invention of the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, signified far more than just a new technology. Their films, such as La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon and L'Arroseur Arrosé, laid the cornerstone for documentary aesthetics, their lenses calmly capturing the poetry of everyday life, satisfying humanity's most primitive desires to "record" and "observe."

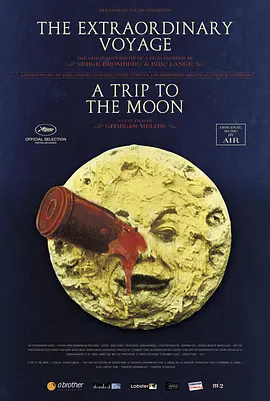

However, if cinema were merely about recording, its artistic life might be limited. Concurrently, another pioneer, Georges Méliès, a true magician and dreamer, infused cinema with the genes of narrative and fantasy. During an accidental camera jam, he discovered the creative use of the "stop trick." From then on, cinema was no longer a replica of reality but a gateway to a fantastical world. In Le Voyage dans la Lune, he integrated theatrical sets, costumes, props, and special effect photography, creating bizarre and fantastical visual spectacles. Méliès established the director's role as the "creator," proving that film could tell a complete, fictional story. During this period, cinema developed along the dual tracks of "recording reality" and "creating fantasy," evolving from a fairground attraction into a new art and entertainment medium with its own unique language, foreshadowing all future possibilities.

Georges Méliès Le Voyage dans la Lune

Lumière Brothers La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon

II. 1920s-1930s: The Avant-Garde Frenzy and Poetic Exploration

After World War I, a mood of skepticism and rebellion against traditional values permeated European intellectual circles. In France, a group of painters, poets, and musicians saw cinema as the most avant-garde arena for artistic experimentation, launching the monumental French Impressionist and Surrealist cinematic movements. The French film scene during this period truly presented a spectacle of "a hundred flowers blooming."

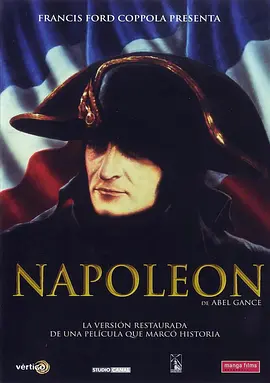

Impressionist cinema did not seek external realism but was dedicated to depicting characters' inner psychology and emotional fluctuations. Representative figures like Abel Gance, in his epic masterpiece Napoléon, used astonishing techniques such as the triptych screen, handheld cameras, and rapid editing to externalize Napoleon's inner turmoil and passion into a visual rhapsody. Surrealism went even further, viewing film as a tool to unleash the subconscious and challenge the shackles of reason and morality.

Abel Gance Napoléon (1927)

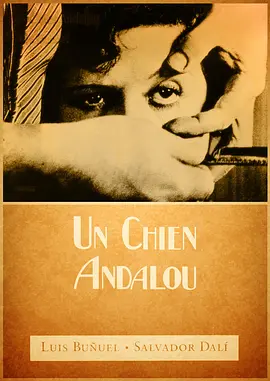

Luis Buñuel's Un Chien Andalou, with its illogical narrative and shocking imagery like the razor cutting an eyeball, directly assaulted the audience's senses and minds, aiming to awaken primitive desires suppressed by civilization. Additionally, films like René Clair's Entr'acte represented the Dadaist spirit of cynicism, deconstructing all meaning with absurdity and humor. Although this movement was mostly short-lived and niche, it vastly expanded cinema's visual vocabulary and depth of psychological expression, establishing French cinema's status as the benchmark for "art film."

Luis Buñuel Un Chien Andalou (1929)

III. 1930s-1940s: The Somber Profundity and Lasting Charm of Poetic Realism

As the clouds of World War II loomed over Europe, the anxiety, pessimism, and sense of fatalism in French society coalesced on the screen into the unique style of "Poetic Realism." This was not a strict school but rather an aesthetic temperament and worldview permeating numerous masterpieces.

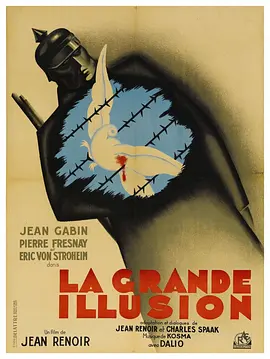

Jean Renoir's pre-war works La Grande Illusion and La Règle du Jeu represent the pinnacle of this style. The former explores the complex relationships between class, nationality, and humanity through a WWI prisoner-of-war camp, filled with humanistic compassion; the latter, like an exquisite comedy, dissects the hypocrisy and decay of the pre-war French upper class, its profound allegory hailed as "a social diagnosis foretelling the fall of France."

Jean Renoir La Grande Illusion (1937)

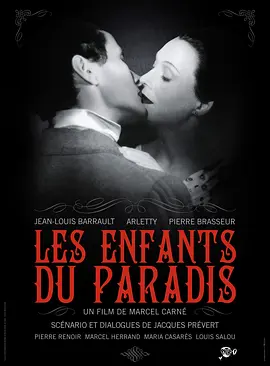

Marcel Carné Les Enfants du Paradis (1945)

On the other hand, the golden partnership of director Marcel Carné and poet-screenwriter Jacques Prévert produced classics like Les Enfants du Paradis and Le Quai des Brumes. These works typically focused on marginalized characters—criminals, wandering artists—whose love was doomed to tragedy, their fates swept along by society and environment. Set within meticulously crafted sets, the films created a damp, dimly lit street atmosphere; beneath the grey realist narrative flowed an ineffable poetry and melancholy. Poetic Realism combined France's profound literary tradition with cinematic language, seeking the light of humanity even under the weight of reality, contributing a body of immortal works of deep thought and artistic maturity to world cinema.

IV. 1950s-1960s: The New Wave Revolution and the Triumph of Auteur Theory

In the late 1950s, a revolution that would completely transform the face of cinematic art erupted in France: the legendary French New Wave. At its core was a group of young critics from the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, such as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, and Claude Chabrol. They raised the banner of "auteur theory," vehemently criticizing the rigidity, conservatism, and detachment from reality of the post-war French "Tradition of Quality" cinema. They argued that the true author of a film is the director, whose body of work should, like a novelist's, be permeated with a unique personal style and worldview.

Technological advancements provided them with weapons. Lightweight handheld cameras and high-speed film stock allowed them to leave the studios and create spontaneously on the real streets of Paris. They employed disruptive techniques like jump cuts, breaking the "fourth wall," improvised dialogue, and natural sound, giving cinema an unprecedented sense of vitality, freedom, and life.

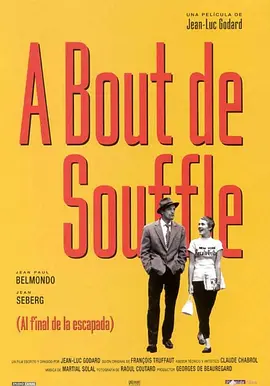

Jean-Luc Godard À bout de souffle (1960)

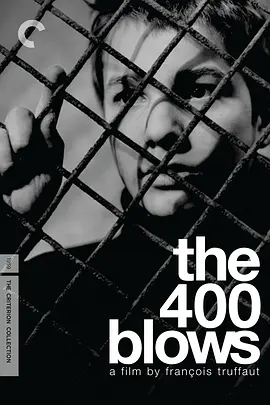

François Truffaut Les Quatre Cents Coups (1959)

Truffaut's Les Quatre Cents Coups explored the pain of adolescent growth with autobiographical sincerity; Godard's À bout de souffle redefined the narrative grammar of modern cinema with its chaotic structure and existentialist themes. The New Wave was not merely an aesthetic revolution; it was also an innovation in production models, proving that low-budget films full of personal will could also achieve commercial and artistic success. This movement swept across the globe like a storm; from Hollywood to Asia, countless filmmakers drew inspiration from it. Its spirit—"film can be made like this"—still resonates today.

V. 1980s-Present: A Pluralistic Landscape and Global Dialogue

Entering the 1990s, especially under the dual impact of globalization and digital technology, French cinema entered a "pluralistic period" difficult to define with a single label. Its core issue became how to maintain its artistic tradition while competing and engaging in dialogue with the increasingly powerful Hollywood commercial empire.

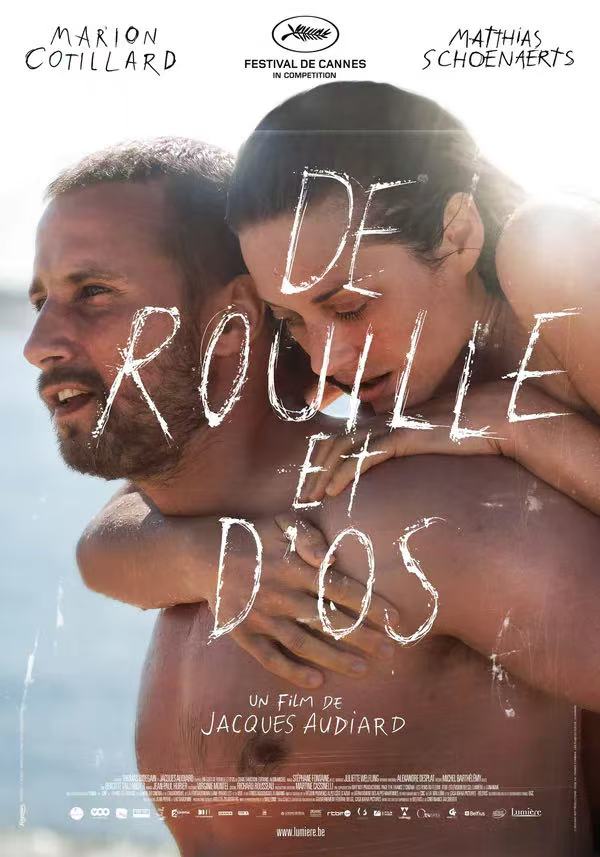

On one hand, the lineage of "auteur cinema" remained strong and vibrant. Masters like Jacques Audiard, with films such as De rouille et d'os and Dheepan, perfectly blended genre elements with an authorial signature, their works repeatedly winning awards at the Cannes Film Festival.

Jacques Audiard De rouille et d'os (2012)

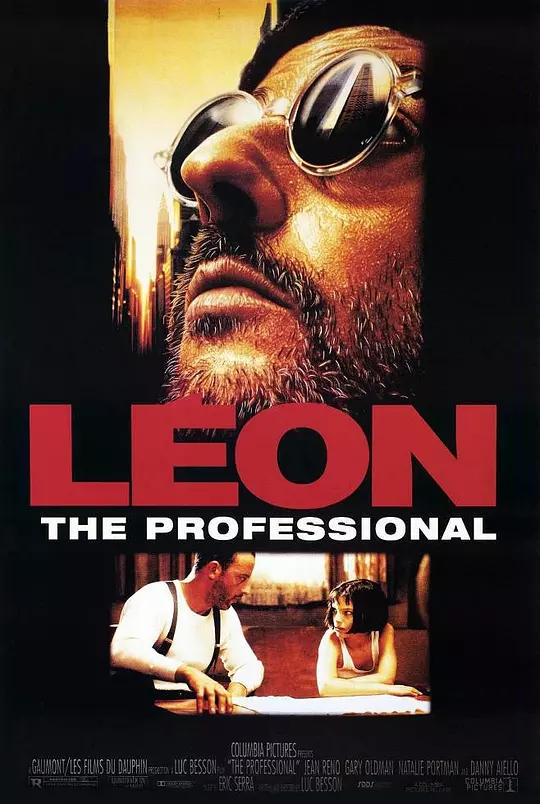

On the other hand, French cinema demonstrated a remarkable inclusiveness of genres. Jean-Pierre Jeunet created a romantic, fantastical Parisian fairy tale with Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amélie Poulain, whose visual style had a far-reaching influence. Luc Besson, with films like Léon and Le Cinquième Élément, proved that French filmmakers could also handle high-concept international blockbusters.

Luc Besson Léon (1994)

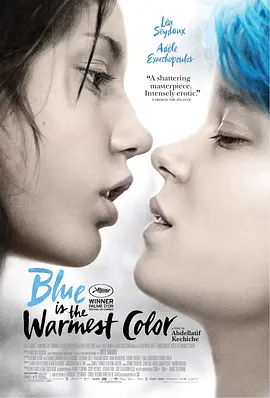

Simultaneously, cultural diversity became a significant characteristic of contemporary French cinema. Numerous directors with immigrant backgrounds, such as Abdellatif Kechiche La Vie d'Adèle and Ladj Ly Les Misérables, turned their lenses towards sensitive issues in French society like race and class, injecting new perspectives and vitality into French cinema.

Abdellatif Kechiche La Vie d'Adèle (2013)

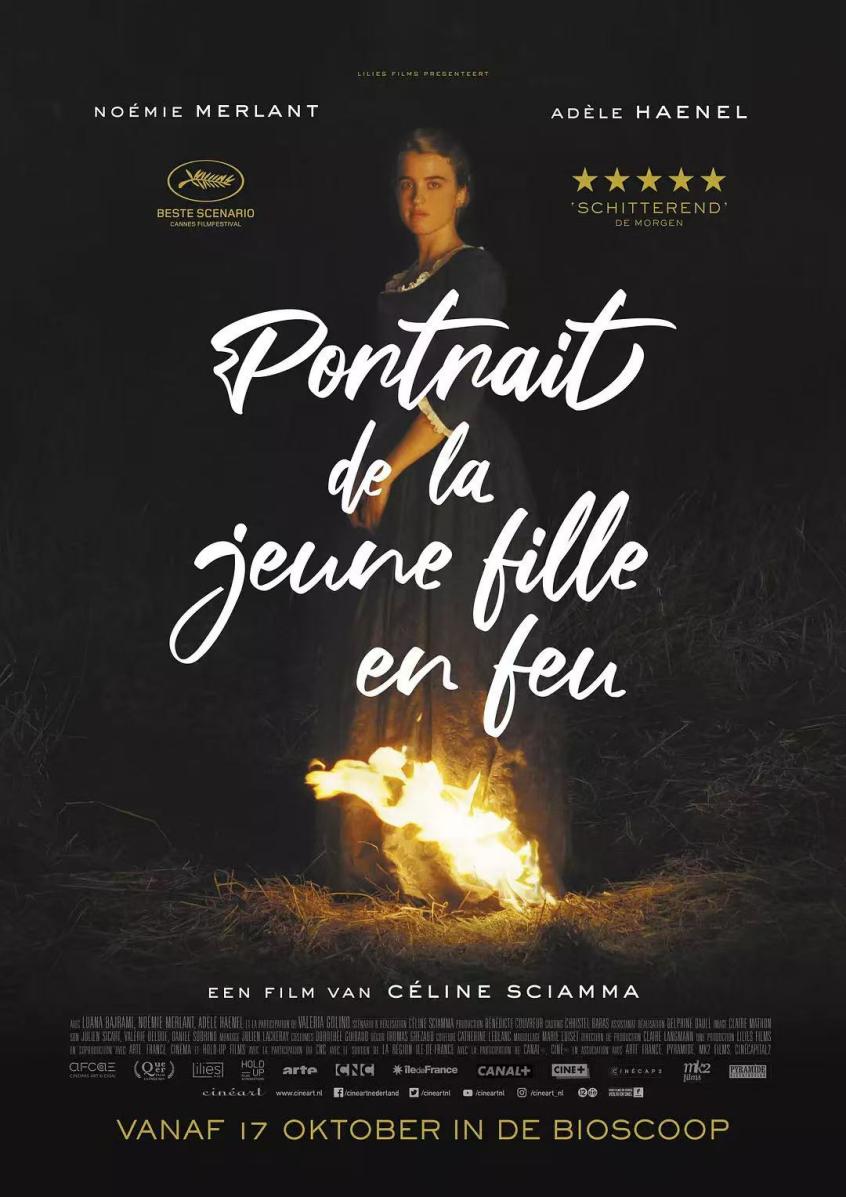

Céline Sciamma Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (2019)

The voices of female directors also grew louder, such as Céline Sciamma with Portrait de la jeune fille en feu, whose works received international acclaim. In this era, French cinema no longer clings to a single "artistic" fortress but advances simultaneously across multiple dimensions: artistic exploration, genre innovation, and social concern. With its openness, resilience, and creativity, it continues to hold an irreplaceable position on the world cinematic map.