China-France Film Co-production: A Sixty-Year Cinematic Dialogue

The year 2024 marks the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and France. Over these six decades, cinema, as the most penetrating cultural vehicle, has not only documented the evolution of bilateral relations but also served as a beautiful bridge for dialogue between Eastern and Western civilizations. From early cultural explorations to today’s in-depth collaborations, Sino-French co-produced films have traversed a unique path paved with creativity and mutual understanding.

As early as 1958, before formal diplomatic ties were established, the film The Magic of the Kite arrived as a transcendent cultural gesture. This fantasy children’s film, co-directed by Wang Jiayi and French director Roger Pigaut, wove an innocent dream connecting Beijing and Paris through a kite adorned with the image of the Monkey King. In the film, the French child Pierrot’s dream journey to China with the help of Sun Wukong was imbued with Eastern mystique and reflected both nations’ yearning for mutual understanding. Like a cultural seed, this work planted the sprouts of friendship even before official diplomatic relations began.

On January 27, 1964, China and France formally established diplomatic relations—a groundbreaking move that reverberated across the world. This was followed by a springtime of cultural exchange. Cinema, as the most influential art form, naturally became a vital channel for deepening mutual understanding.

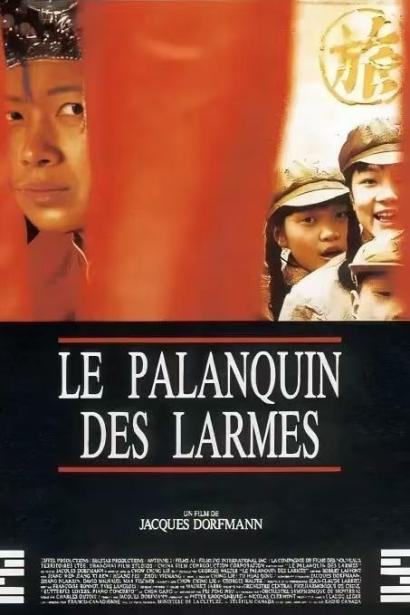

By the 1980s, Sino-French film collaboration reached its first peak. The year 1987 can be called a “miracle year” for co-productions. Le Palanquin des larmes (also known as Tears Of The Bridal Sedan), co-directed by Zhang Nuanxin and Jacques Dollion, portrayed the tumultuous life of French-based Chinese pianist Zhu Qinli, delicately exploring the clash between traditional Chinese family values and Western individualism. The line, “You will succeed, but with whom will you share it?” poignantly captured the eternal theme of cultural identity and personal choice. After its release in France, the film resonated widely, offering French audiences an intimate glimpse into the emotional world of Chinese intellectuals.

图 1The Magic of the Kite 图 2Tears Of The Bridal Sedan

That same year, The Last Emperor became a legend in the history of Sino-French co-productions. Although a multinational collaboration, France’s significant contributions in financing, creative input, and post-production were undeniable. Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, the film interpreted the life of China’s last emperor, , from a Western perspective. It swept the 60th Academy Awards, winning nine Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. This not only marked a major international breakthrough for Chinese-themed cinema but also signified that Sino-French film collaboration had reached world-class artistic standards.

In 1995, Zhang Yimou’s Shanghai Triad continued this positive momentum. The film was selected for the main competition at the 48th Cannes Film Festival, where it received the Grand Jury Prize, and also won the National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Foreign Language Film. This gangster love story, rich with Eastern aesthetic charm, showcased the diversity and artistic maturity of Chinese cinema to Western audiences.

图 3The Last Emperor 图 4Shanghai Triad

In 2010, the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television and the French Ministry of Culture signed the Sino-French Film Co-production Agreement—a milestone in the history of bilateral film collaboration. The agreement provided policy support, financial security, and distribution facilitation, promoting standardized and regularized cooperation.

Under this framework, Wang Xiaoshuai’s Eleven Flowers, directed in 2012, became the first official co-production filmed in accordance with the agreement. Its uniqueness lay in the “split production” model—filming on location in China, with post-production entirely handled by a French team, including editing, scoring, and color grading. This deep technical collaboration broadened Chinese filmmakers’ horizons in international production and reflected a high level of mutual trust in artistic creation.

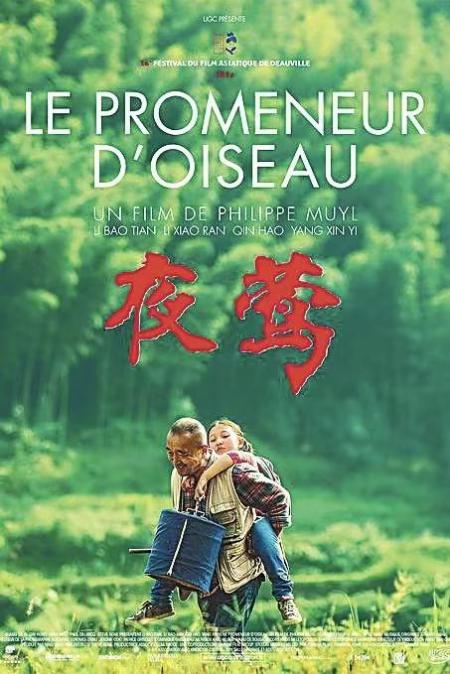

In 2014, French director Philippe Muyl’s The Nightingale became another successful example under the co-production agreement. This emotional comedy focusing on intergenerational relationships in a Chinese family, starring veteran actor Li Baotian, depicted the transformation of families amid China’s urbanization through a grandfather and granddaughter’s journey from Beijing to Yangshuo. The film was well-received in France and praised by French media as “a model of warm Sino-French cultural dialogue.”

图 5Eleven Flowers 图 6The Nightingale

In 2015, the success of Wolf Totem elevated Sino-French co-productions to new heights by combining commercial appeal with artistic excellence. French director Jean-Jacques Annaud, known for his expertise in animal themes and ecological perspectives, adapted Jiang Rong’s best-selling novel for the screen. With substantial investment and meticulous production, the film achieved box office success in China and sparked a viewing craze in France, setting a benchmark for commercial operations among co-productions.

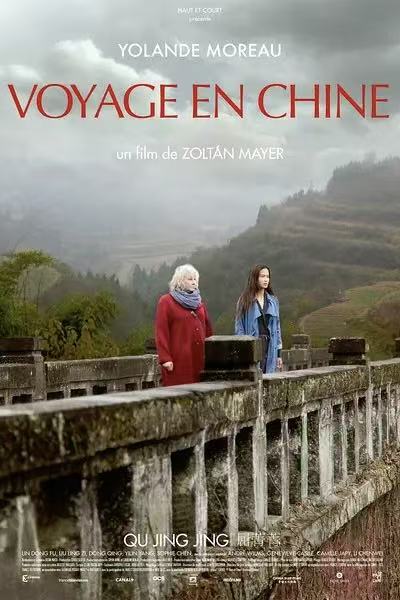

The charm of Sino-French co-produced films lies not only in technical collaboration but also in profound cultural dialogue. Voyage en Chine (2015), created to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Sino-French diplomatic relations, presented the customs and landscapes of southwestern China through the unique perspective of a French mother searching for her son in China. The line, “I tried to follow your trail; better late than never,” expressed the timeless theme of understanding and reconciliation. This narrative of China from an “outsider’s” perspective offered audiences from both countries a fresh dimension of reflection.

图 7Wolf Totem 图 8Voyage en Chine

The Night Peacock (2016) continued director Dai Sijie’s consistent style of blending Eastern and Western cultures. Moving between Chengdu and Paris, the film explored love, art, and identity through cultural symbols such as silk, the shakuhachi flute, and tattoos. The image of the “night peacock” itself represented a perfect aesthetic fusion of Chinese and French cultures.

Last days in Shibati (2017), directed by French director Hendrick Dusollier, documented the demolition and transformation of Chongqing’s old city district. The film won the Louis Marcorelles Award and the Youth Jury Award in France, highlighting the social concern and artistic value of Sino-French documentary co-productions.

In 2024, to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Sino-French diplomatic relations, the documentaryKangxi and Louis XIV was released. The film revisits the friendly exchanges between the two monarchs over three centuries ago, showcasing the long-standing cultural exchange through chapters on technology, trade, and intellectual culture. It is both a tribute to history and a vision for the future.

图 9Last days in Shibati 图 10Kangxi and Louis XIV

Looking back on the 60-year journey of Sino-French film co-productions—from the initial attempts of The Magic of the Kite to the global sensation of The Last Emperor, from the innovative model of Eleven Flowers to the commercial success of Wolf Totem—these works collectively form a history of cultural exchange between China and France, written in light and shadow. They are not only artistic achievements but also testaments to the mutual understanding and respect between the two peoples.

As the waves of the Yangtze River and the ripples of the Seine reflect each other on the silver screen, and as a new generation of filmmakers continues to write new chapters of Sino-French friendship with innovative perspectives, we have every reason to believe that cinema will continue to build bridges of understanding and friendship between China and France. In 2025, Communication University of China will join hands with French partners to organize the “Yangtze Affection · Green Journey” cultural exchange activity. With a new round of cultural exchanges beginning, Chinese and French filmmakers will continue to use the lens as their pen and the screen as their paper, writing more cross-cultural stories that transcend mountains and seas—just like the timeless “kite,” cinema will carry the friendship and dreams of China and France, soaring freely in the sky of civilization.